Debate night on the Internet of Things - report

On 12 December 2023, Privacy First organised a debate evening on the Internet of Things (IoT for short), and how it affects our privacy. This involves 'smart devices' that communicate with each other (and users, as well as companies and governments) via the internet. From doorbells to thermostats and from connected cars to cameras and sensors in smart cities. What is the privacy impact of that?

Four speakers gave enlightening presentations and the audience debated animatedly, led by moderator Hein Wils. Below is a summary of the evening.

By Henk Boeke

Responsible Sensing Lab

Moderator Hein Wils introduced himself as a contributor to the Responsible Sensing Lab: an initiative of the City of Amsterdam and the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Metropolitan Solutions (AMS) to explore how smart technologies can be responsibly applied in the urban environment. In particular, how to think of alternatives to all those cameras and data, which provide much more information than is strictly necessary.

What is it about?

Jurjen Lengkeek (founder IoT Academy) laid the conceptual foundation for the rest of the evening: what is it all about? After a brief introduction of the IoT Academy - a foundation that provides support in developing IoT applications - Lengkeek described the stormy development the technology has undergone, with components becoming smaller, more powerful and cheaper. Followed by an overview of the devices what you can think about with IoT, especially for home use. (Lengkeek is a big fan himself, but acknowledged that it often doesn't work well yet).

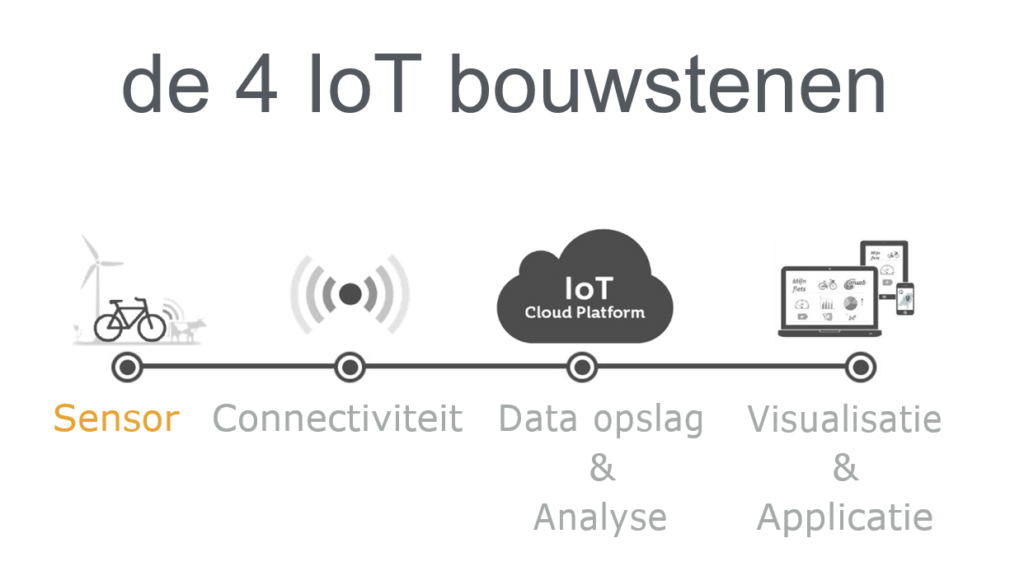

Central to Lengkeek's talk was his model that provides insight into the building blocks that make up each IoT solution, and how they relate to each other - sequentially:

- it always starts with a sensor, that measures something in physical reality (which can also be 'a button', which is measured whether it is on or off);

- through some form of connectivity (wireless and/or via a cable), the data from the sensor go to the internet;

- found somewhere on the internet (on the 'IoT cloud platform') data storage & analysis of data take place;

- finally - at visualisation & application - the result of the analysis presented to the user, who can then do something with it.

With each of these building blocks, something can go wrong in terms of privacy; Lengkeek gave examples of this.

Privacy challenges

Ruben Brave (chairman ISOC EN) explained what the Internet Society (ISOC) is about: an NGO that strives for an open, neutral, decentralised and universally accessible and reliable internet. Among other things, by developing and promoting standards and protocols for a stable internet. But also by stimulating broad public discussions.

In his presentation, Brave addressed the following issues:

- security, or the security of IoT devices and systems, is critical, with the sheer volume and variety of devices and systems posing quite a challenge;

- privacy is also a challenge, due to the huge amount of data generated by IoT devices. This requires effective and responsible management of how the data is collected, analysed and used;

- interoperability and standards, or standardising data formats and communication protocols, is important for IoT devices and systems to communicate effectively with each other;

- laws and regulations deserves extra attention because of IoT. Consider: surveillance (such as camera surveillance), data ownership (who owns what data?) and liability (who is liable for what?).

- emerging economies (in developing countries) also deserve attention, to ensure appropriate infrastructures and the development of IoT solutions for local needs;

- infrastructure development (such as setting up data centres) is needed to support the growth of IoT;

- IPv6 is indispensable to provide enough IP addresses for all those countless IoT devices;

- user empowerment and education are important to teach users understanding and acceptance of IoT technologies.

Especially that last topic - user empowerment and education - is crucial to let citizens keep a grip on their privacy. Which immediately evoked many critical responses from the audience, because how do you organise that?

By special request of the speaker, we briefly mention three more ISOC sources (especially important also in relation to the practical organisation of user empowerment):

- Open letter to election programme committees 2023

- Call: support The Privacy Collective's lawsuit against the illegal sale of your browsing habits

- Internet of Things (IoT)

Smart cities in practice

Vivien Butot (Researcher EUR) is a social geographer, conducting PhD research on how citizens experience 'smart cities' in practice. This revealed remarkable results. Especially that administrators think they are using smart (IoT) technologies to enhance the liveability of their cities, while in practice this often turns out very differently.

Preliminary conclusion of the study:

- that, on the one hand, there is a lot of talk about smart cities needing to focus on their citizens;

- while, on the other hand, it appears that these discussions (and the practices that stem from them) actually exclude citizens' experiences and reactions.

One of the main problems is that drivers want to use available (IoT) technologies for purposes for which the technologies were never intended. For example: the surveillance cars that check license plates to spot parking violations. Couldn't these also immediately flash whether illegal waste is dumped next to waste containers? In itself quite understandable, such a new application, because illegal placement of waste is a real problem. However, this ignores the real problem, which is that residents with a low SES (socioeconomic status) usually do not have space to store their waste at home, when the container is full, and often do not have a car to take their waste to an environmental centre.

Central to Butot's talk was Evgeny Morozov's concept of 'solutionism'. In other words, the tendency to identify problems based on the availability of quick technological solutions. Which many city administrators embrace. According to Butot, this gives rise to at least three problems:

- in terms of definition: what do we actually mean by 'liveability' and 'the quality of public space'?

- dissatisfaction and discomfort are effectively ignored (by offering 'smart' solutions, without looking at the underlying problems);

- solutionism stands in the way of true citizen participation, as citizens are invited to participate in thinking about the solutions offered, rather than the (urban) problems.

How to do things differently

Sander Klous (UvA professor and partner at KPMG) delivered his calling card as incoming chairman of Privacy First. With an impassioned speech on IoT and privacy.

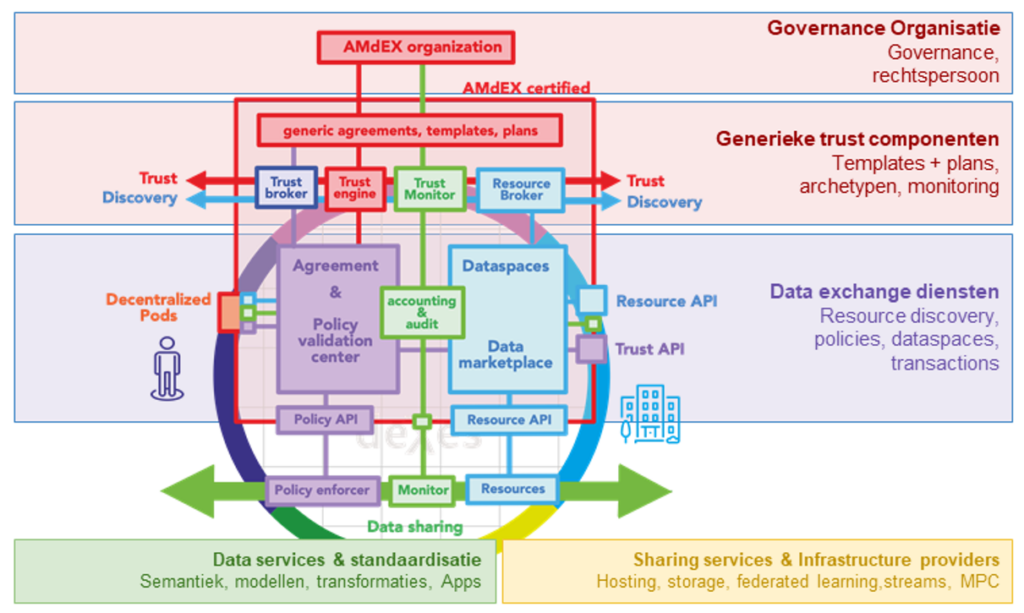

Klous went straight in with a straight leg: that Jurjen Lengkeek's model, with its four building blocks of IoT, really is a bit more complicated after all. With the message: work to be done.

After an illuminating introduction about the closed eco-system of the Apple AirTags, and a plea to build location data into the internet protocol (so that it is available to everyone), Klous concentrated on the possibilities of making medical data truly privacy-friendly. Namely: by synthesising the available data into new (completely anonymous) data. That works. So it can be done that way. And possibly also with IoT data.

Debate

The debate afterwards focused on the citizen, and what they still have a say in their own data. What data is actually collected about him or her, and what is done with it? There was a call for municipalities to clarify this, and Ruben Brave reiterated his thesis that citizens should be informed and educated above all.