Smart street lighting, is it privacy-friendly?

'Smart lampposts' is an umbrella term for street lights that can measure a wide range of things using various sensors. The number of pilots is increasing and there are serious privacy risks.

The most common application is a sensor that measures whether someone is walking by. This way, the lamppost can be turned off when no one is around, to save energy. But the more sensors are added, the more data is collected. It often involves non-personal data, say supporters. But both data activists as ethicists warn of the potential for the types of data collected to still be traced back to an individual. So are our personal data really safe?

Smart lampposts

The discussion about 'smart lampposts' has flared up again since the municipality of Renkum 6300 'dumb' posts are replaced in 2021. These lampposts are energy-saving up to 80%, because they have dimmable LED lights. That sounds like a lie of truth. Saving energy as a goal is certainly good, but not necessarily at the expense of our privacy. For example, you can only put a dimmable LED bulb in a lamppost. The more functions a lamppost has, the more energy it uses. Processing data costs a lot of power. Since 2021, companies and municipalities have been working together to put more 'smart' sensors and functions in the lamppost, such as an electric vehicle charging point and 5G antennas. Those 5G antennas also consume a lot of power. It remains to be seen whether smart lampposts actually save us energy in the long run. Are we giving up our privacy for an empty promise?

Criticism

All these features sound convenient and innovative, but there are also critical voices. In May 2024, a concerned citizen commented on the transparency of decision-making in the municipality of Renkum and the dangers of the poles' surveillance capabilities. So the debate is still alive, as the privacy issue has not yet been resolved. The question of whether the data that lampposts might collect is personal data becomes clear in one of the largest pilots with smart lampposts in the Netherlands, called Stratumseind 2.0.

Stratumseind Living Lab

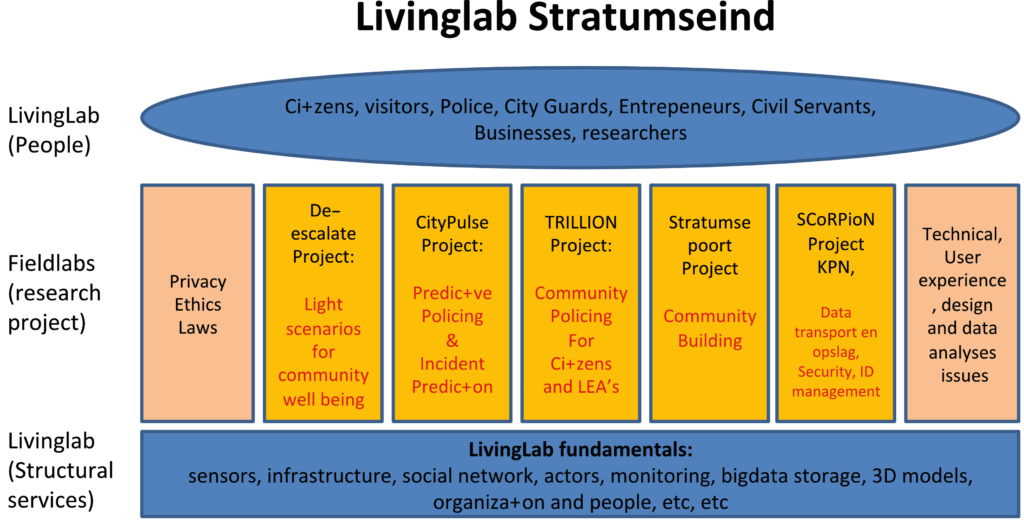

In 2014, a number of pilots started in Eindhoven under the name Stratumseind 2.0, the most important of which was the Stratumseind Living Lab. The project ran roughly from 2014 to 2019 and was a collaboration between Philips and TU Eindhoven.

Stratumseind is a nightlife area in Eindhoven. In the 250-metre-long street, experiments were conducted with light colour, light intensity and even smell. The aim was to make the nightlife street safer. To determine what colour and intensity the lampposts should use at any given time, a kind of profile of the atmosphere was drawn up. This is called two scientists atmospheric profiling. Profiling a person is very often done, think of the information advertisers collect to know who to sell their product to. However, profiling the atmosphere of a street was something new. What is meant by 'atmosphere' is this: people's attitudes, mood, behaviour and interactions with each other and with their immediate environment. In Stratumseind Living Lab, the researchers used anonymised data to create the atmosphere profiles (see factbox). The visitors' nationality and place of residence were anonymised from Vodafone data. How are these data anonymised and who has access to the whole dataset? How long are they stored? This lacks transparency to the public on how this data is used.

The two scientists writing about this warn of developments. As technologies become more sophisticated, it is easier to influence individuals' behaviour. Mood profiles can become increasingly detailed. In the future, a profile of the mood of a small group of visitors or even an individual, for example, could be created. With the rise of AI, it may even be possible in the future to detect emotions through the use of biometrics. Laws are in the works to curb this, but it remains to be seen how effective they will be.

The list of the types of data collected is lengthy and includes:

- the amount of people arriving in and leaving Stratumseind;

- the density of people in the street;

- people's walking patterns;

- the stress level in people's voices;

- visitors' nationality and place of residence (based on data from Vodafone)

- the number of tweets containing 'Stratumseind dates'

- the percentage change in beer ordered by establishments in Stratumseind (per week).

All types of data in this list do not appear to involve data on individuals. But if you happened to be around, they could just be assumed to apply to you. Third-party (e.g. commercial) parties, who do identify you, now have additional context they can add to your personal profile.

Privacy in the law

All data in this pilot was collected without letting visitors know. Anonymised data is not protected by the General Data Protection Regulation (AVG, GDPR in English).

But is anonymised data traceable? And when is personal data actually personal data? There is a debate among law and ethics experts on exactly how to interpret the AVG. Some say that personal are data relating to a person, not just whether the data about someone goes, but also whether the purpose or effect of the data relates to that person. Suppose you are walking through Stratumseind and get into an argument with a friend. It feels weird when you know you are being watched. You then often automatically start adjusting your behaviour a bit. That becomes a chilling effect mentioned. Often chilling effect in the same breath as democracy. If citizens cannot express themselves freely because they are afraid of being filmed at any moment, it is dangerous for democracy. Sometimes surveillance is an effective tool for greater security, but sometimes it threatens to become a tool for disproportionate surveillance. That line is blurred, so it is good to keep evaluating.

How personal is the data collected in Stratumseind? The cameras in Stratumseind may blur the faces of you and a friend with whom you have an argument, then the data collected does not go about you. But the purpose of collecting the data does have to do with you. The goal is to maintain a safe atmosphere on the street and your argument does not fit into that. So if the lights spread a moody orange light or bright white, the people around you also feel the effects of the measures to adjust your behaviour. So the effect also involves people in the street, even if the data does not go about them as individuals.

So there are two major privacy problems in using smart lampposts. The first is that mood profiles can become increasingly personalised, so the protection that was promised is not guaranteed after all. The other problem is whether the data collected by smart lampposts does not infringe on our privacy after all. After all, what if all this data falls into the hands of companies? What if secret services get access to this data? How can we be sure that the data collected will not be used against us as citizens?

Despite these questions, 'dumb' lampposts are being replaced by a 'smart' alternative in more and more places in the Netherlands (and the rest of the world).