The automobile: spy tool and cyber weapon in one

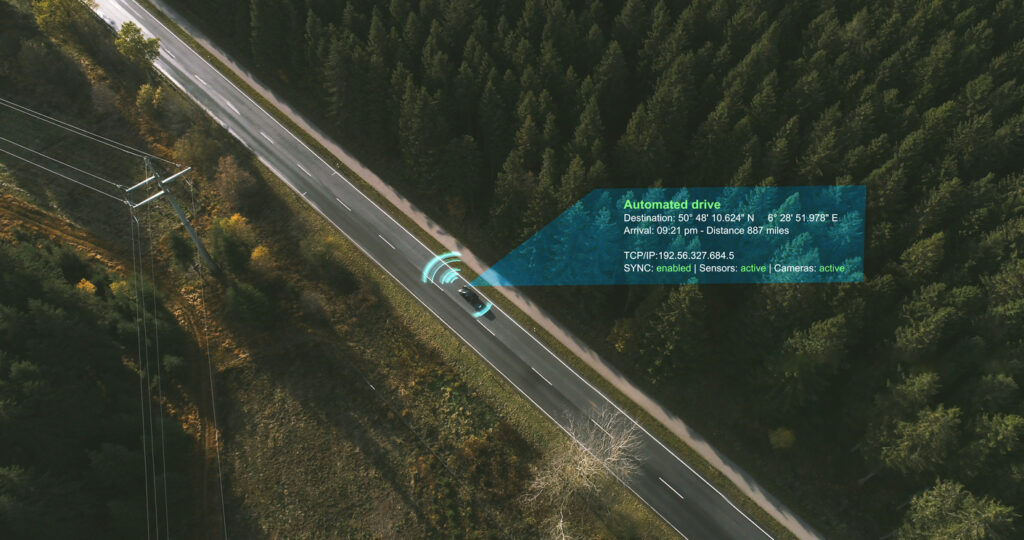

Equipped with SIM cards, cameras and advanced software, modern vehicles are an ideal spying tool for intelligence agencies. Connected cars can reveal a lot about both occupants and the physical environment. Chinese cars arouse suspicion in the West, Western cars scare in China.

This article in five points:

-

Equipped with all sorts of modern technology, contemporary cars can provide insight into the patterns and habits of individuals, but just as easily paint a complex picture of a city, a particular area or critical infrastructure. This makes them ideally suited for spying - an activity that almost always involves blatant invasion of the privacy of one or more individuals.

-

Spying on connected cars can be done via surreptitiously built-in location-tracking SIM cards, but also, for example, from built-in cameras. In the worst case, manipulation of the on-board software could allow the car to be used as a cyber weapon.

-

With the share of Chinese cars on the European market rapidly increasing, many eyes are now focused on China, a country with a bad reputation when it comes to (industrial) espionage. For now, however, the EU is even more worried about the economic question of whether its own car industry will hold up in the long run against vehicles heavily subsidised by the Chinese government.

-

Meanwhile, that Chinese government, for its part, is all concerned about the ability of Western cars to spy in China. Already years ago, it adopted measures that are not even up for debate in Europe. Tesla cars in particular face restrictions, including area bans.

-

Consumers considering buying a Chinese car will mostly have questions about privacy, and want to know if vehicle data is being transferred to China. Answer: not necessarily, but yes, it does happen.

In search of parts that might indicate espionage from Russia or China, British government vehicles were taken apart to the last nut and bolt last year. What was found according to inews? Deep under the bonnet were Chinese sim cards with GPS tracking. Naturally, there are SIM cards in connected cars; after all, this is how cars connected to the Internet communicate with the outside world. But the ones the intelligence services found really did not belong in the official cars of ministers.

The suspicion that another power may well be monitoring the travel movements and destinations of its own dignitaries for years in real-time could track via location-tracking SIM cards, was therefore not unjustified. Lists of coordinates bearing a date and time stamp are very valuable to 'the enemy' because all kinds of sensitive information can be derived from them. It is a sneaky, well-nigh parasitic form of spying via connected cars because the spy devices are not built into their own equipment, but those of others.

The eSIMs of only a few square millimetres detected in British service vehicles were in fact hidden in Electronic Control Units (ECU): small computers that control parts of a car. Vehicles today easily have more than a hundred of these. Many ECUs manufactured in China, not infrequently by companies where the Chinese government has a heavy finger in the pie has. Based partly on warranty and trade agreements, (Western) car manufacturers basically leave those sealed ECUs untouched when installed in their cars, also not necessarily assuming that they would be covertly equipped with SIM cards meant for spying.

Some major Chinese companies produce billions of SIM cards every year. Not much hard evidence has otherwise come out, but some security experts suspect that supply lines of car manufacturers have been compromised because they suspect the Chinese government of ordering the large-scale insertion of SIM cards into ECUs, for example. The underlying tactic? Shooting with hail to later zoom in on a target if desired. Given the extent of the car industry's dependence on China (where many non-Chinese cars are also built), this would create a huge national security problem in numerous countries, because reckon it's not just the UK that would be affected.

At least the British are serious. This is evidenced by the fact that Nexperia, an originally Dutch chip manufacturer that became part of a Chinese group in 2019, last month under government pressure had to sell a plant in Wales due to state security concerns. The plant in question is primarily aimed at the automotive sector and is now owned by US-based Vishay Intertechnology.

Ter contrast over to home country, where Nexperia has just been given the green light to acquire Delft-based chip company Nowie buy up. The acquisition passed the security test for investments, mergers and acquisitions from the Ministry of Economic Affairs. Other recent and related homegrown news: at Eindhoven-based multinational NXP, an even more prominent producer of semiconductors for the automotive industry, Chinese state hackers were found to have spent two years digitally to have broken into and intellectual property stolen.

Higher goal

Gathering intelligence and stealing knowledge and intellectual property is of all times, but as more and more devices and systems are connected to the internet, there has been a significant increase in the number of ways in which (corporate) espionage is possible. Behold the modern vehicle, which, with hundreds of sensors on board, has emerged as an ideal tool for keeping an eye on something or someone. In particular, high-resolution cameras - often barely visible in the bodywork of the car - can be of value in this regard: they provide a 360-degree view and can see tens to hundreds of metres away. So that drivers don't get drunk behind the wheel or fall asleep during a drive, the latest models also include in the interior of the car filmed (more on cameras in the next article).

Connected cars are thus not only data hoovers that put pressure on motorists' privacy, as we have seen in this article series show at length. They can also be used for a 'higher purpose'. Economic or geopolitical motives usually underlie espionage. Who or what the target is just depends. It could be a politician, diplomat, dissident or businessman, for instance. It could just as easily be critical infrastructure or a particular area, such as an embassy district or port. Cars can provide insight into the patterns and habits of individuals, but also paint a complex picture of, say, a city district or industrial area.

As yet, there are no concrete examples that show state actors operating in this way, but technically it is definitely possible. What you see about this in exciting TV series is often an exaggeration of reality, yet never completely out of the blue. In any case, cars are no longer out of place in the spy arsenal of intelligence agencies, consisting of, among others extremely accurate spy satellites, small and large drones, mobile phones and unsecured surveillance cameras which hang in large numbers all over the world and are easy to exploit.

Dams, dykes, bridges and locks

Just to clarify: in the example of built-in SIM cards, spying is not done by but via the car, which in fact acts only as a carrier of the spying device. If it is the car itself that secretly observes or performs something that is not actually intended, it does so using the sophisticated computers and software on board. Either by maliciously pre-programming that software into cars of your own making, or by hacking that (innocent) software into other people's cars and making it dance to your tune. Also possible: not hacking the car itself, but the manufacturer's servers, cloud storage and websites, as we have previously revealed, but with a view to cybercrime. In 85 per cent of cases, cyber attacks take place 'remotely', i.e. not in the physical proximity of a vehicle. This is another way nine-to-five hackers in government service could get revealing or incriminating data.

Initial agreements on cyber security and software updates for vehicles are now in force. These should prevent hacks, spying and malicious applications of software. How do you ensure that cars entering the market (even after updates) do not pose a danger to occupants or state security? That the software in those vehicles follows the rules and absolutely does not exceed certain limits? In other words, not doing anything we don't want. Think about systematically shooting near nuclear power plants or military bases. Or trying to make subversive contact with, say, dams, dykes, bridges or locks, where the car would degenerate into a cyber weapon. It certainly would be in the event of a deliberate crash. All this, in the eyes of some, is a much bigger problem than a car manufacturer knowing where or how fast you drive.

We are almost certainly going to have problems with software that may or may not be controlled by artificial intelligence doing things we feel really should not have done. To prevent this from happening in cars, attempts are currently being made to enshrine this in European type approval. All in all, given the staggering number of lines of code in a modern vehicle (well over a hundred million), this is a huge technical challenge. Powerful control software will be needed to start calculating vehicle software on a large scale. Humans themselves are incapable of doing that.

A set of firm agreements between the major economies on the use of cars as spying tools and especially as cyberweapons could allay fears and suspicions among themselves and reduce the chances of things getting out of hand at some point (soon with self-driving cars?). The likelihood of this, however, is not high. Countries still fail to agree on what the red lines are in the related fields of artificial intelligence and cyber warfare, including the use of killer robots.

Economic danger

Rightly or wrongly, when it comes to spying, many eyes in the West are on China. The fact is that so far it has been relatively small Share of Chinese cars in the European market rapidly increasing. Those vehicles are typically about 20 per cent cheaper than Western-made cars, and are also barely inferior in quality. The future is electric and on that front China is the undisputed leader with last year 64 per cent of global production, and 59 per cent of global electric vehicle sales. China's share of those sales rose by as much as 851 per cent.

Car manufacturer BYD ('Build Your Dreams') is poised to knock Tesla off the throne as the largest seller of plug-in cars. Meanwhile, the global automotive battery supply industry is 90 per cent dependent on China, where the two largest battery producers, CATL and BYD, account for half of the global market. None of this has happened by itself. On the contrary, between 2016 and 2022, China pumped $57 billion into its electric vehicle industry, giving it a huge lead over almost all Western car corporations.

The European Commission is a investigation initiated to the heavily subsidised and thus market-distorting Chinese cars, knowing that it could thereby be heading for an economic conflict with China. A conflict that would be similar to the one several years ago, when it revolved around Chinese solar panels. By the time the EU tried to act against those solar panels, the European market was awash with them and European producers had already been competed away. Under pressure from the European car lobby the EU does not want to make that mistake again. With Europe's car industry at stake, the stakes are also many times higher.

Double standards?

In view of Chinese cars, the main concern is thus the survival of its own car manufacturers, cherished in many a European country as the industrial pride of the nation. Proportionally, though, there seem to be just a little less concern - publicly at least - about the risk of espionage and the threat to the privacy of European citizens. This is striking. In comparison, there was more fuss about (smart) Chinese security cameras which (appear to) hang everywhere. About TikTok, which is used by countries worldwide partially captivated has been done. And, of course, about Huawei, which was forced out of the market in the US and Europe under intense US pressure and was excluded from participation to infrastructure projects concerning 5G.

Given the large-scale industrial espionage which China has been guilty of for decades, there is definitely something to be said for this. An overly narrow focus on the totalitarian China however, obscures the view of the espionage and surveillance capabilities of Western intelligence agencies. The not unjustified distrust in Chinese equipment contrasts sharply with the, generally, blind trust in hardware and software from the United States, a country known for friend and enemy to be structurally tapped. But this aside.

China more wary than Europe

Whereas Australians, meanwhile, are being urged by security experts to Chinese cars to be ignored, such messages are hardly proclaimed in Europe for the time being. Meanwhile, the Chinese government - which in turn is all concerned about the ability of Western cars to spy in China - has long since taken measures that are not even under discussion in Europe.

Since 2016 mandatory China all car manufacturers, including Western ones, all kinds of vehicle data from electric cars sharing with the government. Since 2021, they are obliged to inform the government about what data they collect on their Chinese riders. In addition, they are allowed to collect virtually no more sending data out of the country. Certainly no video images, location data and other data that reveal information about roads, buildings and infrastructure. Tesla (which has a large factory in Shanghai) promptly took a Data centre in China in operation To comply with the new rules.

That brand in particular has repeatedly proven to be the bitten dog in China with (ad hoc) area bans. Thus, Tesla's banned from military bases and are not allowed to go near where summits take place. Military personnel and those employed by key state-owned enterprises are also banned from driving a Tesla. With more than half a million Tesla models on the road in China, the US group is clearly seen as a threat to state security. The question is how long it will be before other brands also come under fire in similar ways.

The Chinese government is keen to minimise any risks as much as possible: 80 per cent of high-resolution cameras in Chinese cars must be installed by 2025 made in their own country. The same percentage applies to the use of radar systems, which cars are also equipped with today. Beijing also wants all satellite navigation technology used in the country to be Chinese by 2030.

Ironically, on its way to technological autonomy, China cannot do without the expertise of Western car manufacturers. For instance, telecoms company China Unicom has been working with BMW, Jaguar Land Rover, Volkswagen and Volvo on developing 5G in cars to be used in real-time sharing data with other cars, infrastructure and cloud services.

Do vehicle data end up in China?

Since Chinese cars are the focus of this article, it can't hurt to also address a pressing question that owners of such vehicles are probably concerned about: will my data be transmitted to China or not? The answer to this is not a resounding yes, but Chinese citizens and companies are in principle, in the context of national security and other considerations, to obliged to hand over data to the Chinese government. This also applies to Chinese companies that have their data on servers outside China, such as Chinese car manufacturers in Europe. Transmitting data to Beijing is in itself a piece of cake.

If you are considering buying a Chinese vehicle but are concerned about your privacy, you would do well to read the highly readable book published last month examination of Top10VPN on it. Using handy summary tables, it looks at the following 10 major Chinese car manufacturers there: Aiways, BYD, GWM (Great Wall Motors), HiPhi, MG (SAIC Motor), Nio, Polestar (Geely), Volvo (Geely), XPeng and Zeekr (Geely).

To what extent are they affiliated with the Chinese government? What kind of data do they collect and what happens to it? How privacy-friendly are their cars and associated apps? And how transparent are they to their customers? Major differences emerge between them on each part tested, but it is clear that each group is failing in one or more ways.

For instance, all brands' mobile apps keep track of more of you than you care about, and the overall privacy policies of seven out of 10 manufacturers are found to be substandard. This includes Polestar, which remarkably cannot present an adequate privacy policy at all. Only MG and Volvo's privacy policies are detailed enough to comply with the General Data Protection Regulation. Five of the 10 brands openly declare to transfer data to China, two hint at doing so, the remaining three fail to say anything about it.

Unknown callers

Finally, we return to where we started this piece: the wonderful world of SIM cards. Indeed, with those things, last year remarkable sth. occurred to Australian owners of BYD's Atto 3. Those drivers scratched their heads and feared for their privacy when it turned out that the SIM cards in their cars could, and actually did, make phone calls. With data-only SIM cards for Internet-of-Things devices should not be possible at all. Unknown callers could therefore listen in on the car, usually without the drivers' knowledge. The only indication of being called was that the infotainment system automatically switched off any audio output. There was no option to disconnect. The shortcoming was reportedly quickly fixed by the Australian telecoms company Telstra, which - outside BYD - is responsible for the SIM cards and had initially misconfigured them. Evidently, no malicious intent was involved here, but could another form of spying via SIM cards have just been uncovered via this incident? If that is a reality, it is hardly reassuring and one might wonder what else is possible that we do not know about.

Next time: the related topic of connected cars and surveillance.