Connected cars: a favourite target of hackers

The more software and communication technologies are put into cars, the more opportunities there are for hackers to attack those cars. Despite the advent of vehicle cybersecurity legislation, sensational car hacks and large-scale data breaches at car manufacturers continue to this day.

This article in five points:

-

Every year, millions of cars are recalled due to defects. Many of these defects are software-related.

-

Errors in software and an increasing number of communication technologies (attack surfaces) make connected cars vulnerable to digital attacks.

-

Many dozens of notable car hacks have made headlines over the years.

-

Car manufacturers also often appear to be inadequately securing their cloud storage, data centres and websites, for example. Anyone who successfully breaks in there can easily gain access to entire vehicle fleets, as well as large amounts of motorists' personal data.

-

New standards and rules should ensure improvement, but only apply to the latest models. In particular, millions of connected cars that have been on the market for some time will remain vulnerable.

''The only truly secure system is one that is switched off, cast in a block of concrete and located in a lead-lined, locked room with armed guards - and even then I have my doubts.'' With those words, the well-known computer scientist and cybersecurity expert expressed Eugene Howard Spafford once his scepticism about the idea that there would be such a thing as 100 per cent security in the digital domain. Any system programmed and built by humans can also, in principle, be cracked by humans.

That certainly applies to cars - especially connected cars, which, while becoming increasingly sophisticated, are also increasingly more vulnerable for digital attacks. Hyundai and Kia came up with a software upgrade for more than eight million US vehicles early this year to halt an increase in car thefts in the United States. Indeed, videos circulated on TikTok and other social media explaining how to easily hacking and stealing.

In our previous article we explained that in modern vehicles it's all about software, but that this software is full of - mostly innocent, 'sleeping' - bugs. Bugs that can be awakened in certain, unusual situations and cause havoc. However, software bugs not only pose a danger to the proper functioning of the vehicle, they also put cybersecurity at risk. Car companies are regularly forced to recall large numbers of cars to fix flaws. If that involves millions of units - which is not unusual, see for example this up-to-date dashboard from recalls in the US - is a very costly affair.

Manufacturers are required by law to disclose recalls when the safety or health of occupants, or the environment is at stake. Defects that 'merely' hurt the car owner's wallet or, at worst, shorten the life of the vehicle, need not be reported anywhere. The website Re-Calls.eu tracks all announced car recalls in Europe. In 2022, 209 models from 37 brands were recalled for a wide variety of defects. Sometimes these are defects that are only mechanical in nature, but often the issues (in addition) have to do with software.

Worst case scenario

So much cutting-edge technology on four wheels is naturally an open invitation for hackers to figure out the extent to which vehicles can be subverted. Like a PC, a connected car can become infected with malware, or, for example, succumb to a buffer overflow attack. In doing so, an attacker exploits the car by placing more data in a memory buffer than space allows. Thus, data in adjacent memory locations can be overwritten, leading to the execution of malicious code, and thus unpredictable behaviour or even crashes.

The worst case scenario is, of course, that a hacker - which, incidentally, is also a state actor as a secret service can be - takes over your car while you are driving on the highway, leaving you helpless behind the wheel. However, the chances of this happening to you as a random motorist are extremely small. Technically, it is possible, but for now it is mainly something out of exciting series. Out of the total number of vehicles on the road, the number of hacks is negligible and insurers do not keep separate statistics. The analogy with healthcare does not apply: if you have poor health, insurers are less willing to insure you, but if your car has poor security, this is not yet a problem.

Wunderwuzzi

Yet there is a clear tenor in the notice on car cybersecurity: connected cars are as leaky as a basket. The examples of car hacks are indeed legion: the one successful attempt some more notorious then the other. Most cases, however, involve attacks from ethical hackers, which sometimes even put their own car under fire. Ultimately, manufacturers can take advantage of this.

A (non-complete) overview of such white hacks can be found in this presentation from Martin Schmiedecker, an engineer at Bosch. It shows that many such attacks take place during special conferences. Soon there will be one in Amstelveen (ASRG-AMS). At the conference organised earlier this year in Vancouver Pwn2Own researchers from security firm Synacktiv managed to get themselves through Bluetooth provide unrestricted access to Tesla's infotainment system.

Whereas that happened in a controlled environment with the cooperation of the car manufacturer, hackers - regardless of their good or bad intentions - usually go completely their own way. So did David Colombo, a German Wunderwuzzi with good intentions who became world-famous in 2021 at the age of 19 by accidentally discovering weaknesses in TeslaMate: a data logger that you, as a Tesla driver, can host yourself and use to collect all kinds of data from your car. In this way, Colombo managed to digitally invade more than 25 Tesla cars in different countries, monitor them (including routes taken) and take over some of their functions. He contacted the owners of the affected models and Tesla itself to warn of the leak. He later described his modus operandi in detail in a blog post.

Just two months ago, another discovered, anonymous hacker ('Greentheonly') that Tesla's have hands-free capability for autonomous driving. At issue is an apparently secret, already built-in but not yet activated feature that the hacker 'Elon Mode' is called - after Tesla boss Elon Musk. Although hackers repeatedly manage to bypass Tesla's security, that security is according to Greentheonly in recent years did improve tremendously and also rare good compared to other car brands.

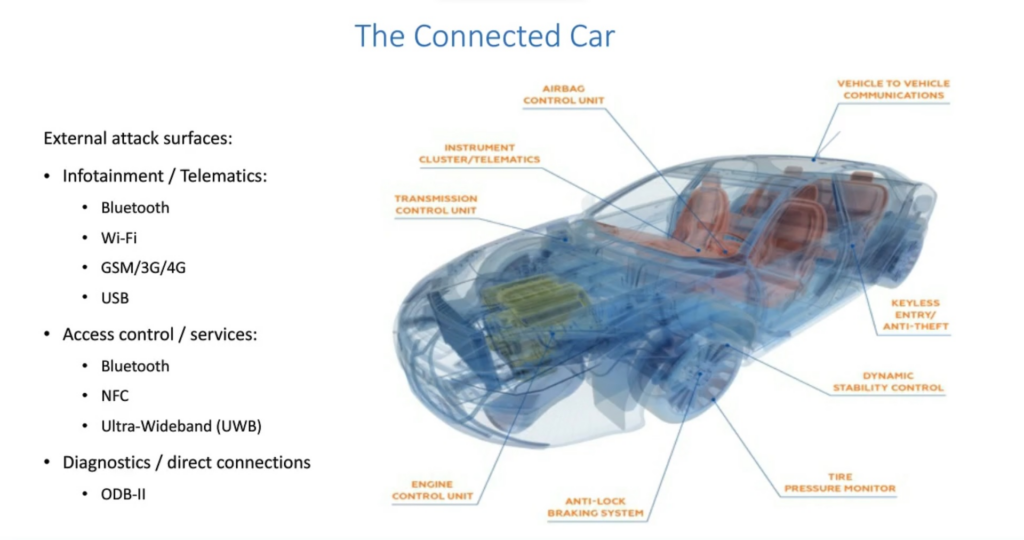

Attack surfaces

The fact is that more and more opportunities are to invade a car: the number of attack surfaces - that is, (communication) technologies that are potentially not foolproof - increases in cars. Direct access to a car is possible by connecting appropriate equipment to the OBD II port, which allows the 'brain' of the car, the CAN-bus, can be read and adjusted if you know the CAN protocols. This is basically what mechanics do in a garage. That way, you can, for example, secretly adjust the mileage downwards.

More interesting and conspicuous are the hacking attempts that involve gaining wireless access to the in-vehicle-network. This can be done with lack of security via the car's Bluetooth or WiFi signal, via the 4 or 5G connection, or, for example, using the radio frequency identification (RFID) signal used for things like keyless entry, immobilisers and the tyre pressure monitoring system (which is reportedly unsecured in many cases). An attack in one of these categories does require physical proximity to the vehicle, otherwise you cannot capture the signal.

In the past, the dashboard infotainment system in particular (WiFi and/or Bluetooth) offered an easy entry point for hackers, as it was usually connected to the rest of the car. Nowadays, that system is (pretty much) separated from the vehicle's other vital functions with their own control units. Among themselves, though, many of those units are connected for specific reasons. In many cars, for example, the doors lock automatically as soon as the first gear change is made when driving off. A modern car easily has a hundred endpoints that communicate with each other and with external networks.

For the sending data from a car manufacturers make use of (private) Access Point Names (APN) from the telecom providers they have deals with for 3, 4 or 5G. With such an access point, mobile devices (in this case the connected car) are in principle securely connected to the car company's corporate network. But because the telematics control unit - which transmits vehicle data - and the APNs are not always set up carefully, hackers can sometimes easily access the data, as was seen a few years ago described by Pen Test Partners, an English company that tests safety systems. A telematics control unit of one particular car model of one particular make that the firm was investigating was found to give access to numerous other cars, note also of other makes. The telecom provider in question had failed to make any separations in this. An extreme example, but still.

Privacy nightmare

However, many car hacks take place not so much by cracking a vehicle itself, but the official app associated with the model, or third-party apps that provide certain services in the vehicle. Above all, a proven 'success': vulnerabilities in servers, websites or databases (and associated API's) from car manufacturers, as the aforementioned David Colombo did. A group of US benign hackers also got it into several car brands early this year with some difficulty together on the basis of so-called 'privilege escalation attacks'. In the process, as an intruder, you appropriate more and more rights to view and modify things.

Once you are inside such a domain as a hacker, you not infrequently have access to entire fleets of cars. And more or less free to do whatever you want with them. In this sense, it may turn out to be easier to break into an entire fleet than to hack into one specific car. Chances are you will also mountains of motorists' personal data will find.

Most (malicious) hackers will be particularly interested in bulk volumes of valuable and marketable personal data. Car manufacturers know a staggering amount about their customers. Mozilla (known for web browser Firefox) did yet another exposé on this last week, citing modern cars in a new research (based on the US market, not the more strictly regulated European one) an outright privacy nightmare. What is a nightmare for some (possibly without knowing it themselves) is a goldmine for others. In 2021, the leaked data of 3.3 million US Volkswagen and Audi drivers were put up for sale on a notorious hacker forum offered.

Clumsy mistake, big consequences

Sometimes, malicious parties are made very easy. For instance, the (vehicle) data, including location data, of over two million Japanese Toyota drivers were more or less up for grabs until May this year. For ten years, the world's largest carmaker had failed to notice that through a human error his home cloud storage was set to 'public' instead of 'private'. A carelessness with potentially big consequences. It also just goes to show: there is no privacy without security. Any privacy policy, however ambitious, is only as strong as the security system behind it.

Another recent example is at least as gnarly. While this did not involve a car company, it did involve numerous motorists: in June appeared that the Amazon-hosted database of Shell Recharge - Shell's global network of hundreds of thousands of electric car charging stations - was not password-protected and could be accessed by anyone via a web browser. It involved nearly a terabyte of names, e-mail addresses and phone numbers of lease drivers using Shell's charging stations, as well as the names of fleet managers, including police forces.

The numerous suppliers on the cluttered charging station market all require installing an app, creating an account and thus sharing all kinds of data. Unless you have a charging station at home, you won't escape this as an electric driver. Filling up at a petrol station is certainly not anonymous, but from a privacy and security point of view it is just a little less sensitive because you don't need an app or account for it, and a petrol valve, unlike the charging port of a plug-in car, is not a attack surface.

The counterattack

In short, it is imperative for car manufacturers to secure their entire chain as well as possible and permanently: from the attack surfaces from a vehicle itself to the entire backend: websites, data centres, the cloud and so on. And making sure that all suppliers also comply with the standards (car companies remain ultimately responsible towards consumers anyway). Standards and rules in this area were absent for a long time, but now some things have been agreed, and the counterattack has begun.

In 2017, the Automotive Security Research Group created, which in 2021 resulted in an industry-agreed upon ISO standard (ISO/SAE 21434) for cybersecurity in cars. That same year, a special United Nations working group which is working on harmonising rules for vehicles, for legislation on cybersecurity (management). That legislation, known as 'R155', could be worded much more sharply, but is a good first step.

Without going into the details: ISO/SAE 21434 and R155 are complementary and mutually reinforcing. Security by design should be the starting point within the automotive industry, parties should stick to coding guidelines for structured programming (Misra C/C++, AUTOSTAR or, for example CERT C), manufacturers must have an incident response plan ready, and security must be in place both chain-wide and throughout a car's lifetime. To this end, connected cars must be connected to a cyber security management system (CSMS) so that they are continuously protected against cyber attacks. That CSMS must be given the green light at the type approval.

Never trust, always verify

Since August this year, under new legislation, garages and car companies in Europe have certificates needed to work on all car parts related to theft prevention. If a car company's paperwork is in order, it will receive a universal certificate. This has been agreed within the Forum for Access to Security Related Vehicle Repair and Maintenance Information (SERMI). There are voices in Brussels calling for such a certificate system - very similar to the well-known Zero Trust-model ('never trust, always verify') - should also be mandatory for the purpose of overall cybersecurity of cars. This would go one step further than currently required.

All automotive players - software vendors, app builders, players on the aftermarket, you name it - would then be certified using Private PKI certificates. Only those parties with a certificate 'get into the car'. Hackers then get a lot harder, because they don't have a certificate. And certificates can be secured in such a way that it becomes very difficult to crack them. There is technology where the certificate changes on an ongoing basis (just like some QR codes change every few seconds), so then as an attacker you are actually hacking an outdated certificate every time. Should a hacker unexpectedly manage to do so, that person is only one vehicle in, not others as well.

Based on certificates, you can see exactly who has been working on a vehicle. If something is not right, you immediately know: it was that person or that person. You can tell by the certificate name. You can always see who is approved and who is not. The certificate must be inspected per operation by a trust centre, an independent third party. Certificates are issued at the vehicle level, so any attempt to penetrate such a trust centre would, at most, result in access to a single vehicle. The question then becomes: how interesting is it for hackers anymore? How much time and effort is an attacker willing to put into exploiting that one vehicle?

Shooting holes

All in all, improvement is in sight, but it is too early to say to what extent carmakers across the board will retaliate for cybersecurity performance that has previously proved underwhelming. Hackers who have been able to indulge until now will not en masse trickle down. On the contrary, they will attempt to poke holes in any new layer of security.

Moreover, R155 only applies to new cars entering the market since 1 July 2022. Not retroactively also for tens of millions of connected cars that were introduced before that date but will last for years to come. Those do not have to meet cybersecurity requirements, and in many cases those vehicles do not. That alone will be a reason why car hacks are likely to remain the order of the day for the foreseeable future.

Software updates, whether or not over the air, may rectify some things. But manufacturers are not required to make such updates for the entire lifetime of those 'older' models under R155, so they may well stop doing so after a few years - just as the operating systems of older phones and PCs stop being updated at some point.

There is much more to say about software updates, including from a cybersecurity perspective. We will do so in our next article.